This story was originally published on The Paper Gown, Zocdoc’s patient blog.

_________________________________________________________________________

Recently, we decided to take a look at patient and physician gender and the relationship between them. Research has shown that a physician’s gender, and whether or not it lines up with that of a patient, can have an effect on treatment outcomes. A study published in PNAS last summer, for example, revealed that both male and female heart-attack patients fared better — i.e., were more likely to survive — under the care of female doctors. The findings were based on 580,000 patients admitted to Florida hospitals for myocardial infarction over a 19-year period. While researchers found a survival-rate bump for all patients treated by female doctors, the difference was pronounced for patients on the XX end of the gender spectrum.

The study doesn’t prove that women are better off seeing female doctors, said lead study author Brad Greenwood, a professor of information and decision sciences at the University of Minnesota Carlson School of Management. But it does reinforce the idea that doctors need to understand the way that factors like gender, as well as race, might affect how health conditions manifest in different patients.

When patients arrive at the ER in the middle of a heart attack, they probably don’t choose the doctor who does their cardiac catheterization. But on Zocdoc, patients have total say over who examines them. We wondered if patients, particularly women, show any preference for providers of their own gender when they’re calling the shots. With help from Amaya Caballero, a data consultant and epidemiologist, we looked at a year’s worth of anonymized Zocdoc data — more than 3 million appointments booked between July 2017 and July 2018 — to see how gender factors into physician selection.

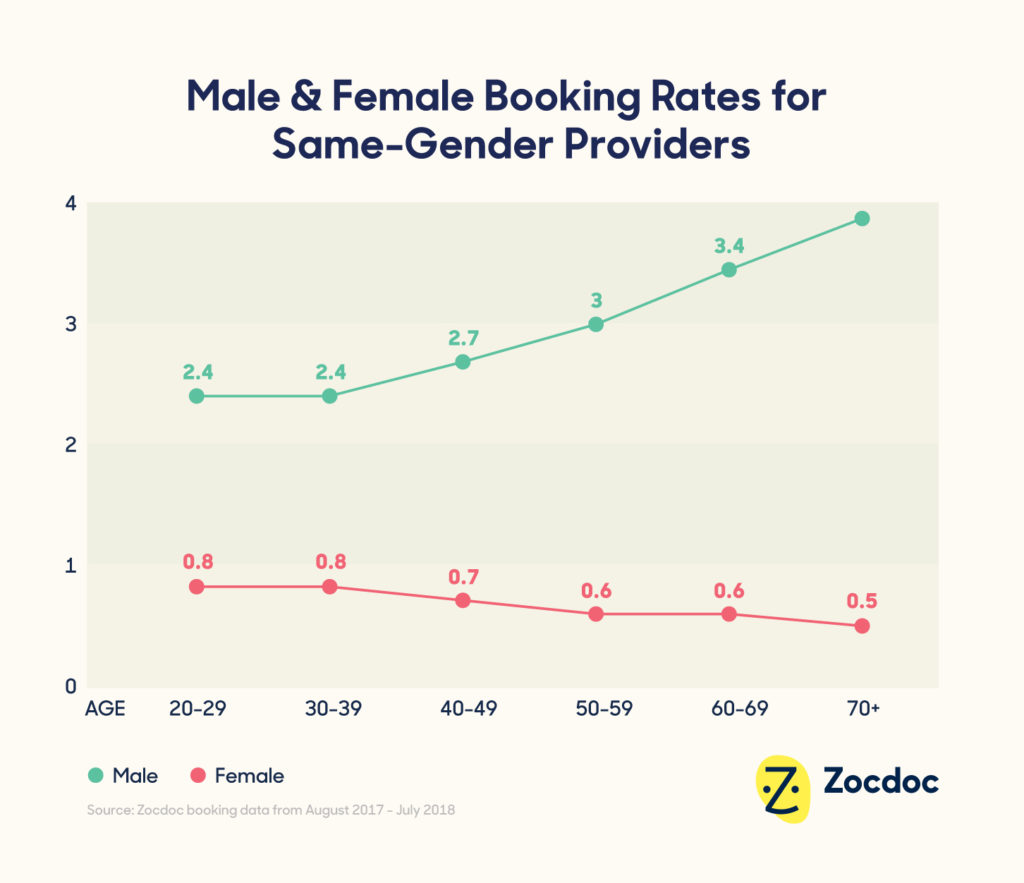

An interesting trend emerged: While younger female patients chose female doctors more often than not, their allegiance to women declined gradually with age. The older female patients were, the more likely they were to see male doctors. As for men, they favored male doctors from the post-college years through the golden years, and their same-gender preference increased with age too.

The only age group where male and female patients both favored female doctors was patients 19 and younger. We can assume that many if not most of these appointments were made by parents. And as Jessica Greene, a professor of health policy and statistics at Baruch College who’s studied physician selection bias, explained, research suggests that in families with a mom and a dad, it’s usually Mom who makes the kids’ healthcare decisions.

Caballero used the under-19 crowd’s preference for female doctors as a baseline and then assessed how older patients’ choices stacked up. Only women in their 20s showed a preference for female doctors comparable to that of younger patients; starting at 30, the odds of women choosing a same-gender doctor fell. Caballero also looked at the raw percentages of appointments with male and female doctors booked by patients in different groups. The same trajectory emerged: Older women opted for men.

Our analysis does have limitations. The Zocdoc patient pool is disproportionately heavy on certain demographic groups, such as millennial women and New Yorkers. So we can’t assume our findings are applicable to the general patient population.

We also employed a binary definition of gender. That means we don’t know anything about the gender preferences of patients who don’t identify as male or female but checked a box because they had to. Research that explores how patients make healthcare decisions using a more nuanced conception of gender is warranted.

One thing we do know is that the age-related shift toward male doctors isn’t solely driven by the types of doctors younger and older women see. Some specialties, like gynecology, cardiology and urology, are disproportionately heavy on one gender, but Caballero looked at the data with and without bookings for those specialties. The association between doctor gender, patient gender and patient age bore out no matter how Caballero sliced the data. In other words, there’s a reason to believe that something beyond “there just aren’t a lot of female cardiologists” underpins our results.

That “something” could be a combination of a lot of factors.

Every expert I talked to had the same question: Do our results reflect the availability of male and female doctors on Zocdoc?

“Availability” isn’t a straightforward issue. Overall, Zocdoc has about the same number of male and female doctors, and patients book appointments with both genders at similar rates. During the year-long period we analyzed, 50.2 percent and 49.8 percent of appointments were booked with male and female doctors, respectively. While doctor gender is less balanced within some specialties, Caballero accounted for that in her analysis.

But when patients use Zocdoc to find new doctors, we can’t be sure they always make selections from gender-balanced lists. One major reason is that patients can use various filters to narrow down their search results. This feature lets patients view only those doctors who meet their needs and preferences, but it can also inadvertently leave them with a page of results dominated by one gender. For example, when I search for a sinusitis appointment with a doctor in Manhattan who takes Aetna insurance, sees patients after 5 p.m. and speaks Arabic, my only options are male doctors (on the first page, at least). Dermatologists near me who take Empire Blue Cross Blue Shield insurance and speak Spanish, on the other hand, skew female.

Additionally, and perhaps more to the point, Zocdoc patients can intentionally filter doctors by gender. But most patients don’t use this filter. Our data shows that 1.2 percent of Zocdoc searches are specifically for female doctors and only 0.27 percent for male doctors.

The long story short here is that most patients who find doctors on Zocdoc don’t consciously restrict their options to one gender. And while we don’t know that the same number of male and female doctors appear in every Zocdoc search, we do know that patients end up choosing men and women at roughly the same rate. This suggests that Zocdoc patients are choosing doctors from mixed-gender lists much of the time.

Looking beyond availability, a few experts suggested physician age as a contributing factor. “It may be there are two versions of this,” said Greene. “When people are seeking out a new doctor, they’re more comfortable with someone in their age range. The other is that older patients have stuck with the same doctor for 20 years, who’s about their age.”

The percentage of female doctors has grown steadily over time, so if patients do gravitate toward doctors around their age, then baby boomers are seeing a lot of MDs (male doctors). “Only in the past couple of years has medical school enrollment reached 50:50, roughly, in terms of male to female enrollment,” said Lauren Walter, a ER doctor and professor in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Alabama School of Medicine. “From a pipeline perspective, we still have a marked minority of female physicians as compared to male physicians nationally, within most subspecialties and markedly exaggerated in some, e.g. surgery.”

How patients think they’d feel and how they actually behave may not always dovetail.

Even if older patients don’t care about a doctor’s age, they might care about something like experience, which often mirrors age. Or older patients might prioritize criteria that, while not related to age, nonetheless steer them towards male doctors — for instance, affiliation with academic institutions.

Patient age, for men or women, hasn’t emerged as a significant factor in other studies on gender preference in physician selection. For instance, Walter co-authored a 2016 study on gender bias in the ER in which the majority of patients surveyed — young and old — expressed no preference whatsoever for male or female doctors. The study shed light on patients’ stated beliefs about the importance of their doctor’s gender. But the patients were surveyed on their way out of the ER, after they’d been treated and discharged, and asked if they’d want male or female doctors in hypothetical scenarios. How patients think they’d feel and how they actually behave may not always dovetail. It’s likely, experts said, that older female patients are still influenced by leftover cultural notions of who belongs in a white coat, even if they don’t realize it.

“I think that for the most part, the majority of perceived gender bias and/or physician gender preference is unconscious, built upon previous life experiences and societal expectations,” said Walter. “Generational ‘preferences’ likely exist, and therefore when we look at older women, they are more likely to select a male physician. That’s all they had to choose from throughout much of their lives, and as such, perhaps that’s who they are now most comfortable with.”

Who patients are comfortable with is what matters, says Greenwood. “You absolutely need to trust your doctor and feel comfortable. The medical and epidemiological literature on this is unimpeachable. If you feel more comfortable with your provider, you’re more likely to communicate better. And if you communicate better, you’re more likely to adhere to the prescribed course of treatment.”

If being comfortable means seeking out a doctor of one gender, experts seem to think that’s OK, at least in some cases. “It’s understandable that some patients may deliberately select same-sex physicians for ‘sensitive’ medical issues,” said Walter. “That being said, I believe this is really just a societal mindset, and that undoubtedly, the male ob-gyn and the female urologist are just as competent and with a similar capacity for sensitivity.”